Who decides on a diagnosis and how?

The latest version of the DSM, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), was published in 2022. It involved more than 200 experts (according to psychiatry.org). The original version was discussed and brought together over a period of more than ten years. ICD-11 involved over 300 specialists from 55 countries (according to Wiki) and came into effect globally in January 2022.

I could fill more than one blog post with explanations of how autism is viewed and described in these manuals, but here is one quote which stood out for me, taken from the Autism Europe website:

...the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 do vary in a number of ways. For example, the ICD-11’s classification provides detailed guidelines for distinguishing between autism with and without an intellectual disability. The DSM-5, for its part, only states that autism and intellectual disability can occur simultaneously.

Our daughter has a spiky profile (meaning extreme strengths in some areas alongside extreme difficulties in others) but that wouldn't be classed as an intellectual disability. Does that mean she wouldn't be given a diagnosis of autism by someone who only went by the DSM-5?

The internet is full of brilliant articles which cover and dissect topics like this. I don't consider myself very 'high-brow', so I tend to end up talking in layman's terms. In a nutshell, the term Pathological Demand Avoidance is not in these manuals; neither is Sensory Processing Disorder and yet I don't think the fact that a lot of autistic people have sensory issues itends to be challenged? Asperger's Syndrome (AS) used to be in the manuals (largely because it was 'discovered' over 40 years before research on PDA was first undertaken), but that AS term has now been removed in favour of using the over-arching term 'Autism Spectrum Disorders'. Although I understand the reasoning behind wanting to remove the term AS from general use, I still believe that characteristics relating to Asperger's Syndrome exists, as much as I believe that PDA exists.

So who decides on a diagnosis? Healthcare professionals. Individuals, who may be following guidelines of one manual or another, or both. Diagnosing is a very complex area, which is of course open to human error like most things in life.

Why we believe in PDA

Every time we met though, I heard that their girls were quite different to Sasha in many ways. I'm generalising of course, but on the whole as a group they talked about how their girls liked routine, had obsessions about objects, were 'on the edge' of social groups and more comfortable being on their own, liked to follow rules and were scared of getting into trouble, very black and white about facts and didn't tend to role play or immerse themselves in fantasy worlds.

So whilst I felt welcomed and part of the group, I still felt like an outsider in a way. I still hadn't met anyone else with a child like mine. That's when I researched more on the internet, and stumbled across PDD-NOS (Pervasive Development Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, catchy term, huh?!). This was sometimes also called Atypical Autism, and included a huge variety of characteristics which didn't fall into the kind of behaviours my new group of friends were talking about. A short while later, some more reading online led me to descriptions of Pathological Demand Avoidance, and that's when I had my 'lightbulb moment'.

I returned to the paediatrician who had given our girl a diagnosis of ASD and requested a referral to the Elizabeth Newson centre which was where most experts in PDA worked at the time. We were told there was no funding available to enable us to go there but instead we were offered the chance of further tests at GOSH. Our experiences there are detailed in a few blog posts at that time; this one titled Great Ormond Street visit; High Functioning Autism or PDA? is a good place to start.

In summary we weren't given any change of diagnosis from the clinicians at GOSH. Sasha's paediatrician informed us she was unable to diagnose PDA herself as it wasn't in the diagnostic manuals, but a second line of oppositional behaviours/Pathological Demand Avoidance behaviours was added to her diagnosis letter.

PDA as a label

It has been suggested that it doesn't help to 'label' our child with Pathological Demand Avoidance, particularly if it might not be a 'real' diagnosis. The whole debate about 'labelling' a child with anything is one I've touched on before; those who call it a label are maybe not appreciating the fact that it's a very important signpost, which should be just the beginning of research about any one individual. Research on PDA is a growing area of autism; understanding is still patchy in areas, but what we do know is that the groups of children who were noted by Elizabeth Newson displayed characteristics similar to our girl.

Sociable on the surface: Sasha would literally talk to anyone and seemed to enjoy being around others. I remember her once going over to grab a postman by the hand, even though she had never met him before!

Obsessions with people rather than objects: Sasha had interests such as Dora and Peppa Pig in the early days, and now it's more Pokemon, Nintendo, Minecraft and Roblox, but these were never obsessions. I think that I, as the person who understands her best, have always been her obsession, and over time it's developed to a point where she doesn't want anyone else to carry out certain routines for her, such as bedtime, or getting her food etc.

Vivid imagination and ability to role-play: Sasha still to this day spends a fair amount of time running around 'in her own little world' with imaginative stories and scenarios coming out of her mouth. She's never been a black and white, matter of fact kind of person.

Resisting and avoiding ordinary demands: Sasha refused to do simple everyday things which we knew she loved to do, such as swimming, or going to the park - activities which were not part of our agenda but fun places for her to be. It became obvious that a major cause of the avoidance was the lack of control she felt she had over any given situation.

Using social strategies to avoid instead of simply saying 'no': I still remember vividly the first ever conference about PDA which I attended several years ago. It was held by the National Autistic Society and during the event, a video was played of a young child in clinic, avoiding all the questions put to him by giving answers which wouldn't be expected from a typically developing child. It brought tears to my eyes, as I recognised so many similarities with what our girl used to say and do - she would ignore requests (which led to several hearing checks... her hearing was just fine), she would curl up into a mushroom and pretend to go to sleep, she would give phrases such as 'my legs don't work so I can't'. At times she would change the subject and try to distract the person asking the questions or making demands of her.

These are only a handful of Sasha's behaviours which led us to finding out about PDA; many more examples are scattered through the earlier posts on my blog.

Would I mind if I was told to stop using the term PDA to describe my daughter?

We've completed the EDA-Q (Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire) with regards to Sasha at various times over the years and she always scores highly - that is to say, over 50, which is the point at which a profile of PDA should be considered.

Do I feel that Sasha is exactly like all the other people diagnosed with PDA? No, of course not. I've still never met another child quite like Sasha. Everyone is different, after all. But being part of a community of people who all feel like the term PDA 'fits' them or their child does bring some kind of inner peace, less isolation. Comfort is gained from people who understand the challenges that society presents us with.

Sasha is still young but I am looking forward to the time when she can tell us whether she feels that the term PDA helps her in any way. I do know that being part of the PDA community has helped me and countless other families so far. I see no good reason for others to suggest that the term is taken away, or to deny its existence.

It's important to stress at this point that the purpose of my blog from the very beginning was to share how life is for Sasha, from my perspective. The aim was, and still is, to educate others about Sasha and to consider the impact of her diagnosis on our family life. So I don't claim to speak for everyone, I'm purely giving our point of view. Pathological Demand Avoidance is very real for us.

|

| * this image contains an affiliate link and I may receive a small commission if you use it. It won't cost you any extra. |

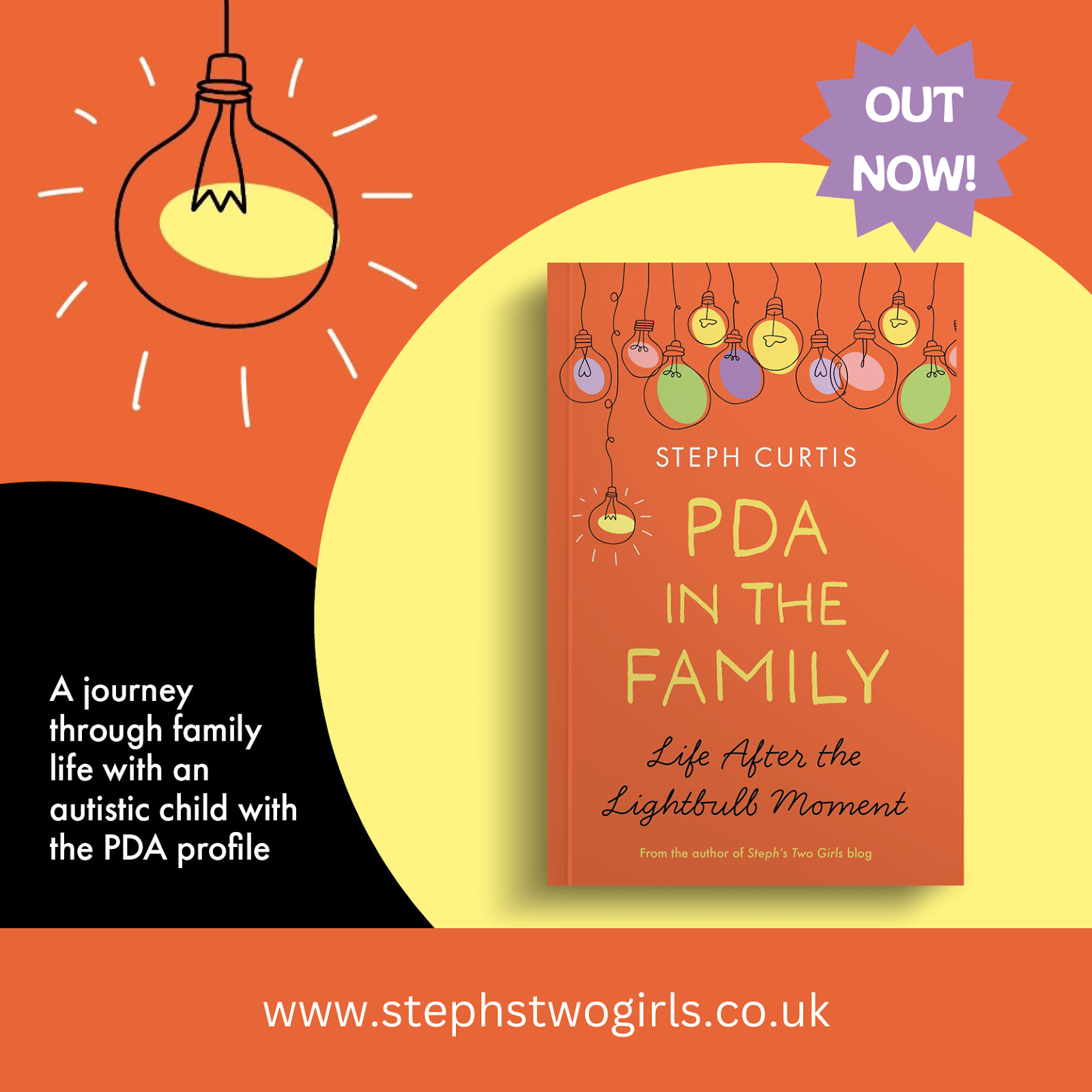

Our book, PDA in the Family, is out now! We wanted to help other people understand more about Pathological Demand Avoidance and this book was one way of doing that. It's an account of how family life has been for us since an autism diagnosis for our youngest daughter, and the subsequent lightbulb moment when we heard about PDA: PDA in the Family: Life After the Lightbulb Moment Book Launch

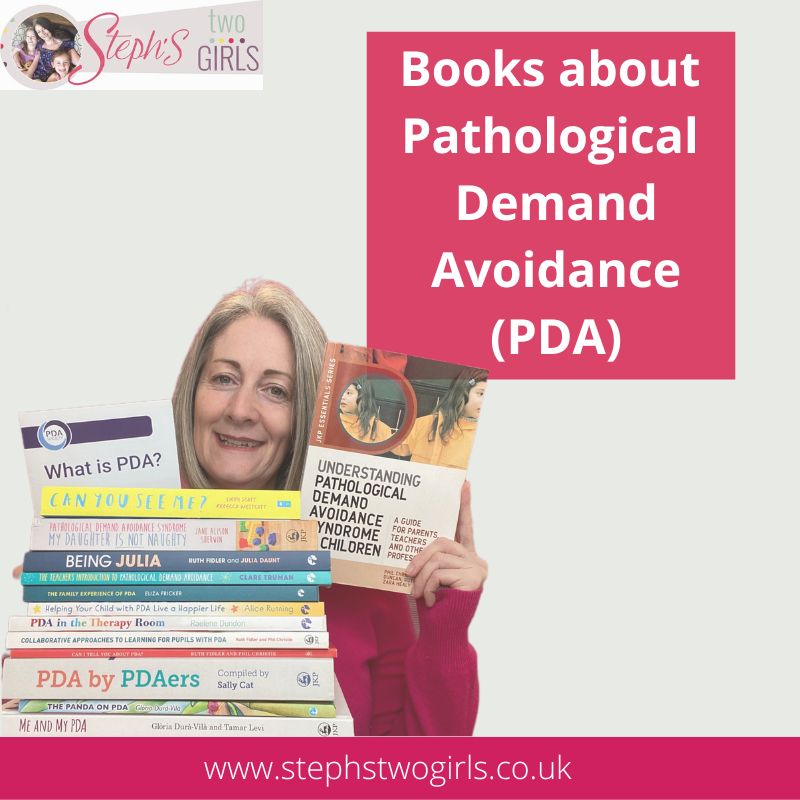

For more books about PDA, click on the image above. To hear more about our story see our 'About Us' page or the summary of our experience in Our PDA Story Week 35. If you are looking for more online reading about Pathological Demand Avoidance, the posts below may help.

- What is PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)?

- Ten things you need to know about Pathological Demand Avoidance

- Does my child have Pathological Demand Avoidance?

- The difference between PDA and ODD

- Strategies for PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)

- Pathological Demand Avoidance: Strategies for Schools

- Challenging Behaviour and PDA

- Is Pathological Demand Avoidance real?

- Autism with demand avoidance or Pathological Demand Avoidance?

- Books about the Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) profile of autism

Anyone who doesn’t think it isn’t real ought to live with it. You do an amazing job and your blog is so informative and relatable.

ReplyDeleteYou have given me a lightbulb moment just today realising that my children have an obsession with me too. That’s quite a though and explains so much! Thank you

Thanks Miriam. Obsessions are difficult to switch away from! x

DeleteI wrote a brief outline of what I thought helped my daughter and what it was.My daughter is 12 and agrees that is what PDA is for her x

ReplyDeleteGreat that she can vocalise it! I think Sasha is nearly at that stage...

DeleteBrilliantly explained as usual. I feel exactly the same way x

ReplyDeleteThanks Kirsty, relieved it made sense!

DeleteHi we've been in crisis with our 14 year old son for 4 months, we have been trying to get him assessed and diagnosed for 10yrs Now, our younger son was diagnosed 5yrs ago ASD and presents PDA, our 14yr old was discharged last week from a child and adolescent Hospital, he is now back under Fresh Cahms who have said they don't diagnose it when I was told they do, just so fed up.

ReplyDeleteSorry to hear this. Ten years is a long time :(Sometimes it's about using the strategies regardless of the diagnosis x

DeleteI think PDA seems to work quite well as a term for describing a specific type of difficulties and needs, for which the strategies needed are often quite specific too. So as I see it, it’s a useful diagnostic term, and helpful. I don’t think people should be asking if it’s ’real’, they should be asking if it’s helpful. Or perhaps just shut up about things they have little knowledge about ;-) xx

ReplyDeleteI agree with you, totally :)

DeleteYou describe everything so well. I have several friends who are always glad when I share your posts. You are changing things with your writing. x

ReplyDeleteThanks so much. You do amazing things yourself ;)

DeleteThank you for the concise explanation. I had to fight for a diagnosis for my son, and eventually got 'mild autism'. I more recently recognised that he has PDA, and the appropriate strategies are so much more helpful.

ReplyDeleteIt's rubbish that people have to fight! Glad you've found the PDA strategies help though x

DeleteFound your article from the U.S. PDA website thank you for the clear explanations and sharing your experiences. I agree that it doesn't matter what you call it. It only matters that it helps others help my child without making him feel bad about himself! Keep up the good work!

ReplyDeleteThank you, I'm happy to hear my blog has helped in some way. The PDA Society are the best source of information.

DeleteHi, I'm dad to x2 ASD boys and they couldn't be more different. Both are what some may call 2E (gifted IQs along with ASD, one with other things as well.) I know things may change in the future, as research on all neurodiversities is still in infancy but as it stands my understanding is that there is no official diagnosis of PDA. That isn't saying my son and your daughter don't present in a specific way, but doesn't every autistic person present differently? I don't like some of the emotional comments that try to say that correctly stating there is no PDA as an official diagnosis means someone is saying that your situation and others doesn't exist because that isn't what all people are saying at all. How does it differ from ODD? ODD is recognised as a diagnosable disorder and is often comorbid with ASD. Until science proves otherwise it feels a little like astrology. It is popular because a lot of people feel warm and fuzzy about what they hear. In my role as a teacher in an alternative setting I do hear the term PDA thrown around a lot and in many cases it encompasses learned behaviours, general disobedience, ODD and of course Autistic kids who react in a certain way. With no official framework and boundaries it is too often a 'cure all' for a bunch of very different things. Sorry if I sound like a real downer but I'm just saying what I see from my experience.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comment - if you check out my Facebook page you'll see a lot of people have shared their thoughts on whether PDA is real. I agree with some of your comment - yes every autistic person is an individual and will have different strengths and challenges. I think you will find that there are people with PDA as an official diagnosis. My daughter would not meet the criteria for an ODD diagnosis - you can read more about that in my post The difference between Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). PDA doesn't make me feel warm and fuzzy (!) but it is the set of characteristics that most closely describe my youngest daughter. She didn't learn this 'behaviour' from us, or her older sister, and there was no trauma that caused it. I only write about our experiences and can't speak for families or children who attend your setting, but I would hope that teachers in alternative settings would have an open mind and listen to parents, and that they would understand that behaviour is the outcome of underlying difficulties and help and support is needed for those (often anxiety based when it comes to PDA).

DeleteDear "Anonymous3 June 2024 at 08:40"

DeleteAs the father of a PDA boy who has been out of school for several months now due to school staff who falsely labelled him as having 'learned behaviours' and who didn't think PDA was real, your commentary 'from your experience' is quite sickening.

It's easy for someone in a school setting to decide PDA isn't real - they don't have to deal with the consequences of their decision, it's the parents that suffer, and the school can just blame the parents for being silly.

ODD is totally different to PDA - yes it has the same behaviours on the surface at times - but the root is not anxiety based - that's the difference. Hopefully by now you've found time to read Steph's very helpful blog on the differences between PDA and ODD and now understand that.

If you treat a PDA child like they have ODD, they'll be out of school within days or weeks, and you as an educator can sit back and blame the parents or the kid and not see the results of your actions - you don't see a child's life being destroyed as they have 1 failed school experience after another, and the parents mental anguish too, and physical hardship as they take time off work to help do what the schools should be doing.

Just because the scientific manuals haven't caught up with reality doesn't mean PDA doesn't exist. Many years ago most people thought the world was flat, I'm told...

I'm not expecting this reply to change your opinion, but I'm hoping it will help someone out there...

MT Steph for your hard work advocating for these extremely vulnerable and highly misunderstood kids!!!